17 Jun 2015

Visual inverse kinematics, Basic understanding : In the previous post we anticipate the problems caused by the gaps and inaccuracies of motors in the inverse kinematics of the robot. Now, in this third post we will talk about the solution implemented during the GSoC15 project.

So, with the inverse kinematics component that we have implemented in Robocomp, we had the problem of inaccuracies and gaps in the robotic arm motors, problems that made the robot believed reach the target position without having actually achieved it. To solve this problem it was decided to implement a solution inside the visual field (which is what concerns us throughout this project), whose aim is to provide the inverse kinematics component a visual feedback that allows correct its mistakes. The operation of the algorithm is very simple and takes as its starting point the investigations of Seth Hutchinson, Greg Hager and Peter Corke, collected in A Tutorial on Visual Servo Control [1].

##’Looking’, then ‘moving’

As Hutchinson, Hager and Corke reflect in their work:

Vision is a useful robotic sensor since it mimics the human sense of vision and allows for non-contact measurement of the environment. […] Typically visual sensing and manipulation are combined in a open-loop fashion, ‘looking’ then ‘moving’.

So the goal of Visual servo control is to control the movement and location of the robot using visual techniques (detection and recognition of objects in an image). To get an idea how it works, we must have clear some fundamental concepts in this field

###Kinematics of a robot

We need to know what a kinematic chain is, what reference system and transformation coordinate are anda what algorithm is executed inside the robot kinematic. These concepts were explained in the second post of this collection. If you have doubts, consult it.

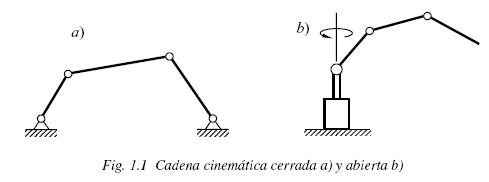

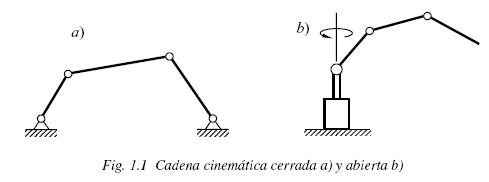

If we link the kinematic chains concept with visual techniques (ie, now, in addition to the chain formed by the motors of the robotic arm, we have a camera in the chain looking one of the chain ends), we have two types of systems:

- Endpoint open-loop (EOL): Systems which only observed the target object. These systems don’t need to look at his end effector so normally the camera is on the end effector (hand-eye).

- Endpoint closed-loop (ECL): Systems which observed the target object and the end effector of the arm.

The visual inverse kinematics that we implemented in Robocomp uses this last configuration because is independent of hand-eye calibration errors (precisely, the clearances errors and inaccuracies that bother us in the inverse kinematics), although often requires solution of a more demanding vision problem, because we need to track the end effector.

###Camera Projection Models

We need to understand the geometric aspects of the imaging process if we want to understand how the information provided by the vision system is used to control the movement of the robot. The first thing to consider is that an image taken by a camera is always in 2D, so we’re losing spatial information (the depth of the scene).

To resolve this issue we have several options:

- We can use multiple cameras that capture the studio space from different positions.

- We can obtain multiple views with a single camera.

- We can have previously stored the geometric relationship between certain characteristics of the target or the elements in the studio space.

In any case, we must keep in mind certain things common to all cameras. For example the system of axes: the X and Y axes form the basis of the image plane and the Z axis is perpendicular to the image plane, along the optical axis of the camera. The origin is located on the Z axis at a distance λ of the image plane. That distance λ is what we call focal length.

We can map the position and the orientation of the end effector in space calculating the projective geometry of the camera. But this method, complicated in itself, increases their difficulty because we need recognize the end effector in the picture, in addition to deriving the speed from the changes observed in each frame that the camera capture. For these reasons, in our visual inverse kinematic component, we use the algorithm proposed by Edwin Olson, Apriltags [2] a visual fiducial system that uses a 2D barcode style tag (binary, black and white synthetic brands), allowing full 6 DOF localization of features from a single image. Thus, if we put a apriltag in the end effector, we can get its position and orientation in a very simple way.

##visualBIK component

Having already some clear concepts, let us study how the component developed in this project, visualBIK, works.

Our component implements a simple state machine where waits the reception of a target position (a vector with traslations and rotations: [tx, ty, tz, rx, ry, rz]) through its interface. When a target is received, the visualBIK send it to the inverse kinematics component like a POSE6D target, and waits for him to finish running the target and placing the arm. As the end effector will be a little out of the target position (due to inaccuracies), the visualBIK will be prepared to correct this error:

- It calculates the visual pose of the end effector (through apriltags, visualBIK receives the position of the end effector mark that the camera head sees).

- After, it compute the error vector between the visual pose and the target pose.

- With this error vector, visualBIK corrects the target pose and sends the new position to the inverse kinematics component.

- This process is repeated until the error achieved in translation and rotation is less than a predetermined threshold.

In this way we can correct the errors introduced by the inaccuracies of the joints.

This component (like component inverse kinematics) is still in the testing phase and is more than likely suffer some changes that improve its operation.

Bye!

[1] Hutchinson, S., Hager, G., Corke, P. A Tutorial on Visual Servo Control, IEEE Trans. Robot. Automat., 12(5):651–670, Oct. 1996. Download in http://www-cvr.ai.uiuc.edu/~seth/ResPages/pdfs/HutHagCor96.pdf

[2] OLson, E. AprilTag: A robust and flexible visual fiducial system, Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2011 IEEE International Conference on, 3400-3407

15 Jun 2015

What is inverse kinematics? : In this second post, although it may seem begin the house from the roof, let’s talk about how a robot moves its arms and hands in order to manipulate daily objects.

The ultimate goal of this work is make the robot to be able to recognize certain daily objects in a house (for example a mug), and to manipulate these objects with its effectors (hands). To do this, one of the things we need to implement is the inverse kinematics of the robot. Although this is the last step, we start by inverse kinematics to be easier and more intuitive than object recognition (besides that we have almost finalized the cinematic component in Robocomp).

###What does the inverse kinematics?

A recurring problem in robotics is to give to robots a certain autonomy in terms of movement. Focusing on a practical and realistic example, as is the trajectory of a robotic arm from an initial position to a target point, the question is how does the robot move its arm from the starting pose to the final pose? or what values take its engines arm to reach the final position? This is the typical problem of inverse kinematics, which is responsible for calculating the angular values of a kinematic chain composed engines (joints) of the arm to reach a target position.

But before we get down to work, we need to review a few concepts.

###Previous concepts

####kinematic chains

The first concept that we should be clear is the kinematic chain. The kinematic chain is a set of elements that produce motion, deforming the chain to adapt it to movement. Kinematic chains are composed of two elements:

joints: joints or motors that produce the movement. Each joint gives a degree of freedom.links: rigid segments that connect the joints together.

An example of kinematic chain in robotic is the arm of the robot, that is composed by all the motors that the robot has and the segments that connect this motors in order to create the arm form.

####Reference systems and Transformation coordinate.

One of the problems of robot manipulators is to know where their structural elements are arranged in the space in which they move. We therefore need a referral system that puts or position the elements of the robot in the workspace. So, a reference system is a set of agreements or conventions used by an observer to measure positions, rotations and other physical parameters of the system being studied. In our case, the arm of the robot is into the three-dimensional workspace (R³, with the axis X, Y and Z), where each components (for example, each joint) has one traslation (tx, ty, tz) and one rotation (rx, ry, rz). Therefore, the position of each component is given by a vector of six elements: P=[tx, ty, tz, rx, ry, rz] (the first three translational and three rotational recent). Normally, we represent the poses by homogeneous trasnformation matrices, which are of the form:

where R is the rotation matrix and T the traslation coordenates.

One of the kinematic problems is that each motor (which can be moved and/or rotated with respect to the previous motor of the chain) has his own reference system, so if we want to calculate the position of a particular point or joint, we will have to make a number of changes (transformations) to move from one reference system to another. For example, if we have the newt arm:

X_1--------------X_2--------X_3-----O

M_1>2 M_2>3 M_3>O

where X_n represents the position of the joints, - is the link that connects the joints, o is the end effector of the arm and M_n>m are the transformation matrices to change the reference system n to the system m, and we want to calculate the position of the end effector in the reference system of the joint X_1, we have to calculate this equation:

Po_inX_1 = M_2>1 * M_3>2 * M_o>3 * Po_inO.

###Problems to solve the inverse kinematics.

If the forward kinematics is responsible for calculating the position of the end effector in a kinematic chain, given some angular values for the joints, the inverse kinematics is just the opposite: it is responsible for calculating the angle values of the joints so the end effector reaches a position. This last problem is much more difficult to solve. So difficult that we are forced to use generic mathematical methods that try to approach an optimal solution iteratively within a reasonable time. We have opted for an iterative method known as the Levenberg-Marquardt or damped least squares algorithm. This method is used for solving nonlinear least squares problems where a solution to decrease an error function is sought.

###Inverse kinematics in Robocomp

As a result of the TFG, Inverse kinematics in Social Robots [1], since 2014 Robocomp has a component [2] that is responsible for calculating the inverse kinematics of the social robot Ursus [3], developed by Robolab. This component has undergone a big evolution, since it was created last year to now, and is more than likely to continue evolving to achieve inverse kinematics each finer and in less time.

Originally, this component receives three types of targets:

- POSE6D: It is the typical target with translations and rotations in the X, Y and Z axis. The end effector has to be positioned at coordinates (tx, ty, tz) of the target and align their rotation axes with the target, specified in (rx, ry, rz).

- ADVANCEAXIS: its goal is to move the end effector of the robot along a vector. This is useful for improving the outcome of the above problem, for example, imagine that the hand has been a bit away from a mug. With this feature we can calculate the error vector between the end effector and the mug, and move the effector along the space to place it in an optimal position, near the mug.

- ALIGNAXIS: Its goal is that the end effector is pointing to target without moving to it but rotated as the target. It may be useful in certain cases where we are more interested in oriented the end effector with the same rotation of the target.

To solve these various inverse kinematic problems, the component uses as main base the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm proposed in the article SBA: A Software Package for Generic Sparse Bundle Adjustment by Lourakis and Argyros:

Input: A vector functon f: R^m → R^n with n≥m, a measurement vector x ∈ R^n and an initial parameters estimate p_0 ∈ R^m.

Output: A vector p+ ∈ R^m minimizing ||x-f(p)||^2.

Algorithm:

k:=0; v:=2; p:=p0;

A:=transposed(J)·J; error:=x-f(p); g:=transposed(J)·error;

stop:=(||g||∞ ≤ ε1); μ:=t*max_i=1,...,m (Aii)

while(!stop) and (k<k_max)

k:=k+1;

repeat

SOLVE (A+μ·I)·δ_p=g;

if(||δ_p||≤ ε2·(||p||+ε2))

stop:=true;

else

p_new:=p+δ_p

ρ:=(||error||^2-||x-f(p_new)||^2)/(transposed(δ_p)·(μ·δ_p+g));

if ρ>0

stop:=(||error||-||x-f(p_new)||<ε4·||error||);

p:=p_new;

A:=transposed(J)·J; error:=x-f(p); g:=transposed(J)·error;

stop:=(stop) or (||g||∞ ≤ ε1);

μ:=μ*max(1/3, 1-(2·ρ-1)^3);

v:=2;

else

μ:=μ*v;

v:=2*v;

endif

endif

until(ρ>0) or (stop)

stop:=(||error||≤ ε3);

endwhile

p+:=p;

Where A is the hessian matrix, J is the jacobian matrix, g is the gradient descent, δ_p is the increments, ρ is the ratio of profit that tells us if we are approaching a minimum or not, μ is the damping factor, and t and ε1, ε2, ε3, ε4 are different thresholds. But the IK component of Robocomp adds several concepts to the original L-M algorithm, in order to complete the proper operation of the component:

- Weight matrix: that controls the relevance between the translations (in meters) and rotations (in radians) of the target. So, where

g was calculated as transposed(J)·error, now g is transposed(J)·(W·error)

- Motors lock: when a motor reachs its minimun or maximun limit, we modified the jacobian matrix.

The new version of the inverse kinematics component simplifies the code of the old version and adds some more functionality:

- Executes more than once a target. The inverse kinematic result is not the same if the start point of the effector is the robot’s home or a point B near tho the goal point.

- Executes the traslations without the motors of the wrisht (only for Ursus). This makes possible to move the arm with stiff wrist, and then we can rotate easely the wrist when the end effectos is near the target.

Another improvement being studied is to include a small planner responsible for planning the trajectories of the robot arm, in order to facilitate the work of the IK component and reduce its execution time. However, one of the problems that the inverse kinematics can not solve by itself is the problem of gaps and imperfections of the robot. These gaps and inaccuracies make the robot move its arm toward the target position improperly, so that the robot “thinks” that the end effector has reached the target but in reality has fallen far short of the target pose.

In order to solve this last problem, we need visual feedback to correct the errors and mistakes introduced for the gaps and inaccuracies in the kinematic chain. The visualBIK component, developed during this project, is responsible for solve this visual feedback and correct the inverse kinematic, but we’ll talk about it in the next post.

Bye!

[1] Master Thesis, Universidad de Extremadura, Escuela Politécnica de Cáceres. Mercedes Paoletti Ávila. Cinemática Inversa en Robots Sociales. Directed by Pablo Bustos and Luis Vicente Calderita. July 2014. Download in https://robolab.unex.es/index.php?option=com_remository&Itemid=53&func=startdown&id=143

[2] inverse kinematics component repository: https://github.com/robocomp/robocomp-ursus/tree/master/components/inversekinematics

[3] C. Suárez Mejías, C. Echevarría, P. Núñez, L. Manso, P. Bustos, S. Leal and C. Parra. Ursus: A Robotic Assistant for Training of Patients with Motor Impairments. Book, Converging Clinical and Engineering Research on Neurorehabilitation, Springer series on BioSystems and BioRobotics, Editors, J.L Pons, D. Torricelli and Marta Pajaro. Springer, ISBN 978-3-642-34545-6, pages 249-254. January 2012. Download in https://robolab.unex.es/index.php?option=com_remository&Itemid=53&func=startdown&id=128

[4] Lourakis, M. I., Argyros, A. (2009). SBA: A Software Package for Generic Sparse Bundle Adjustment. Article of ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software, volume 36, issue 1, pages 1-30. Download in http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/1486527

12 Jun 2015

##What is a binary package?

A binary package in a is an application package which contains (pre-built) executables, as opposed to source code. Basically a binary package is an archive which contains executables some other info like rules on how to install them, dependencies etc. debian binary package is also a type of binary package. You can use a package manger to install these packages.I have explained I have explained it in tutorial Debian packaging.

##Implementation in Robocomp

For binary packages i was left with two options. whether i could use the same cmake script i used for creating source packages or i could use the CPACK packaging tool. Finally i decided to go with CPACK because - 1)less code , that means less messing up 2)its an well known tool so is expected to perform better than a script i am writing. CPACK has so many configuration options so i made a seperate cmake file package_details.cmake for configuring cpack so that its easier for users to change any configuration. CPACK will add a target package for generating binary package. so you could run make package for generating the package.

##Source packages and ppa

A Personal Package Archive (PPA) s a special software repository for uploading source packages to be built and published as an APT repository by Launchpad.So basically if a software has a ppa then users can just add the pa to their sources and they will be able to install the software package and will also get updates automatically. As alreasy mentioned we can only upload source packages into a ppa, by definition Source packages provide you with all of the necessary files to compile or otherwise, build the desired piece of software. now the next question is how can we create source packages. I have explained it in tutorial Debian packaging.

##Implementation in Robocomp

For creating source package for robocomp i wrote a cmake module source_package.The module will basically copy the source in to another directory (currently Debian in build folder) and will create the source tar.Then it will create all debian/ files dynamically. The script will be executed when the target spackage is made.

After creating the source packages one trouble i faces was in setting up (registering) the PGP keys. Once you have created a launchpad account you should sign the Ubuntu Code of Conduct.Then you can upload the package using dput utility.

###NB

-

Unfortunately CPACK has a bug in it, its not changing the control files permission correctly which throws a warning during installation. so i have create a bash script which will fix the control file permissions.

-

You cant upload a package with same name into same ppa again, launchpad will reject it. so you need to change the package name and hence the version, every time you upload. This is automatically taken care off by the script.

-

If there are any changes to the source, then you should upload the whole source into the ppa. Well, any changes to fies in debian folder is not considered a source change. In Robocomp its implemented in such a way that if there is any changes to the source, then you have to change the Robocomp version.

-

Right now we are not generating the changelog automatically. But that is a feature we could add, generating changelog from the git commit messages.

Nithin Murali

12 Jun 2015

About Me : Hello! My name is Mercedes Paoletti Ávila, and I would like to introduce me a little in this first post. I’m graduate in engineering from the University of Extremadura, and currently I study the Master in computer engineering and ICT management in the same University. Over the past two years I have been working in the Robotics Laboratory of the UEx, Robolab. There I developed my end grade work, “inverse kinematics in social robots”, using the robotic framework implemented by the laboratory, Robocomp, and now I’m doing my Master’s Thesis, that is about robots planners and is part of the project of LJ Manso, AGM.

And just following this course of action, this project combines the two concepts (planning and inverse kinematics) for recognizing and manipulating objects, using the framework Robocomp.

##Symbolic planning techniques for recognizing objects domestic

The main object of this project is the application of symbolic techniques to build efficient pipelines in order to improve computer vision techniques, recognition and interpretation of domestic objects, to be finally executed on a domestic robot, so that the robot is able to move around a house and identify and interact with any objects located inside. The goal is that given a high-level task (eg. “grab a mug”), we can use symbolic planning techniques to build a pipeline of visual processing.

In order to reach this goal, we need some previous concepts:

1) We need a planner to organize the sequence of commands to be executed by the robot. We will use the AGM planner [1].

2) We need a system to recognize marks or some objects. For now, we wil use the algorithm proposed by Edwin Olson, AprilTags [2]

3) We also need a system that controls the movement of the robot and corrects the calibration errors and gaps of the engines. We will use the inverse kinematics component developed in Robocomp, which will add techniques of trajectory planning and visual feedback.

All this provides a robust support that allows the robot to move freely within a given environment, such as a home, and interact with everyday objects that are in it.

You can acces to the code of these components in the Robocomp repository: https://github.com/robocomp

[1] AGM documentation: http://ljmanso.com/agm/

[2] AprilTags: http://april.eecs.umich.edu/papers/details.php?name=olson2011tags

23 May 2015

We recommend that you create a repository for your components (i.e. mycomponents directory in the example before) in your GitHub account (or other similar site) and pull/clone it in ~/robocomp/components whenever yo need it. For example, if your GitHub account is myaccount, first log in with your browser and create a new repository named mycomponents following this instructions:

https://help.github.com/articles/create-a-repo/

Now is good time to write down a short description of what your component does in the README.md file.

Then we need to clean up the binary and generated files in myfirstcomp. Note that this is not necessary if you upload the component to the repo just after creating it with DSLEditor and before you type cmake .

cd ~/robocomp/components/mycomponents/myfirstcomp

make clean

sudo rm -r CMakeFiles

rm CMakeCache.txt

rm cmake_install.cmake

rm Makefile

rm *.kd*

rm src/moc*

sudo rm -r src/CMakeFiles

rm src/cmake_install.cmake

rm src/Makefile

now we are ready:

cd ~/robocomp/components/mycomponents

git init

git remote add origin "https://github.com/myaccount/mycomponents.git"

git add mycomponents

git push -u origin master

You can go now to GitHub and chek that your sources are there!