20 Aug 2015

At the start of the second term, I finished developing the version-2 of the website.

Version-2 : https://github.com/robocomp/website/tree/version-2

After learning from the previous-2 version built the Version-3(Current) of the website using Jekyll.

Version-3 : https://github.com/robocomp/website/tree/gh-pages

Website : www.robocomp.net

Parallely I started developing simple components for robocomp which would introduce new users to the framework. I have implemented the components in both the languages which robocomp supports - c++ and python. Also have documented the same.

C++ components : https://github.com/rajathkumarmp/RoboComp-Components

Python components : https://github.com/rajathkumarmp/RoboComp-Python-Components

Documentation : https://github.com/rajathkumarmp/RoboComp-Docs

Future : I will be writing starter components for each of the available interface so that a new user can easily get started. After having executed most of the already available components in the robocomp organization, In the coming days I will be working on components using PCL and explore other possibilities with the framework. It has been a great learning experience so far and I am hungry for more. Cheers!

Rajath Kumar M.P

20 Aug 2015

Grasping object : This post will describe the planning system that implements Robocomp in order to provide to the robot a full functionality. In order for a robot be able to carry out a mission as “take the cup from the table and take it to the kitchen,” it needs something that in robotics calls planner. In this post we move away the issue of inverse kinematics and we dive into the field of artificial intelligence, making a slight revision of existing planners and delving into the planner using robocomp.

###Planning

As the name suggests, the planning is to generate plans. Plans to be executed by a robot in order to reach a goal. These objectives are often complex and require the execution of a series of steps that must be organized in the best possible manner to achieve the objective with an effort and within a reasonable time.

In order for a planner can build a series of plans, it needs an initial state of the world, a desired end state (or several) and a set of rules. For example, take the objective of frying an egg. We start with an initial world consisting of a kitchen with the necessary elements: an egg with a dozen eggs, a can of oil, a frying pan, a slotted spoon, a plate and a stove. And we have a set of rules, like to pour oil, to water plants, to crack egg, to stir, to serve, to light fire and to put the fire out. The duty of the planner is to select and order those rules that allow us to go from the initial state of the world (with raw eggs) to the final state in which a fried egg is served on a plate. Thus, the planner would eliminate the rule of “to water plants”, and would order the rest of rules as follows:

to light fire: in order to light the stove.to pour oil: to pour oil into the panto crack egg: to crack the egg and throw it into the panto stir: to catch the slotted spoon and to go stirring the oil for frying the egg well.to put the fire out: when the egg is fried the stove is turned off.to serve: to serve the fried egg on the plate

With these steps (very simplified) we get that our robot prepares us a fried egg… Although the example is miserable, we can see that any action we do and that we find it easy to execute, for a robot is quite complicated. That is why planning is a very complex field of artificial intelligence.

###Planning Domain Definition Language (PDDL)

This section will introduce the reader slightly in the planning language more used in artificial intelligence: PDDL. It was created in 1998 by Drew McDermott and his team for use in that year’s edition of International Planning Competition. The aim of PDDL is to standardize the planning languages for greater reuse of planning domains. Its operation is relatively simple:

Take for example, the following domain to create geometric shapes: We presume that in our initial world there is always a vertex node. The rules increase the number of vertices nodes to create geometric identities. For example, the segment rule creates from the initial node a line segment, the rule triangle creates from the line segment an equilateral triangle, the rule “square” creates from the equilateral triangle a square… and so on until an octagon. In the PDDL file, the rules would be:

(define (domain AGGL)

(:predicates

(firstunknown ?u)

(unknownorder ?ua ?ub)

(isA ?n) # IS A NODE?

(isB ?n)

(isC ?n)

(isD ?n)

(union ?u ?v) # TWO NODES ?u AND ?v are united?

)

(:functions

(total-cost)

)

(:action segment

:parameters ( ?va ?vListAGMInternal ?vlist0 )

:precondition (and (isA ?va) (firstunknown ?vlist0) (unknownorder ?vlist0 ?vListAGMInternal) (not(= ?vListAGMInternal ?vlist0)) )

:effect (and (not (firstunknown ?vlist0)) (not (unknownorder ?vlist0 ?vListAGMInternal)) (firstunknown ?vListAGMInternal) (isB ?vlist0) (union ?va ?vlist0) (increase (total-cost) 1)

)

)

(:action triangle

:parameters ( ?va ?vb ?vListAGMInternal ?vlist0 )

:precondition (and (isA ?va) (isB ?vb) (firstunknown ?vlist0) (unknownorder ?vlist0 ?vListAGMInternal) (not(= ?vListAGMInternal ?vlist0)) (union ?va ?vb) )

:effect (and (not (firstunknown ?vlist0)) (not (unknownorder ?vlist0 ?vListAGMInternal)) (firstunknown ?vListAGMInternal) (isC ?vlist0) (union ?vb ?vlist0) (union ?vlist0 ?va) (increase (total-cost) 1)

)

)

(:action square

:parameters ( ?va ?vc ?vb ?vListAGMInternal ?vlist0 )

:precondition (and (isA ?va) (isC ?vc) (isB ?vb) (firstunknown ?vlist0) (unknownorder ?vlist0 ?vListAGMInternal) (not(= ?vListAGMInternal ?vlist0)) (union ?va ?vb) (union ?vb ?vc) (union ?vc ?va) )

:effect (and (not (firstunknown ?vlist0)) (not (unknownorder ?vlist0 ?vListAGMInternal)) (firstunknown ?vListAGMInternal) (isD ?vlist0) (union ?vc ?vlist0) (union ?vlist0 ?va) (not (union ?vc ?va)) (increase (total-cost) 1)

)

)

)

To represent the initial world from which we start and the final world that we want to go, we should implement a file like this:

(define (problem myProblemPDDL)

(:domain AGGL ) # planning domain ---> set of rules

(:objects

A_1

unknown_0

unknown_1

unknown_2

unknown_3

)

(:init

(= (total-cost) 0)

(firstunknown unknown_0)

(unknownorder unknown_0 unknown_1)

(unknownorder unknown_1 unknown_2)

(unknownorder unknown_2 unknown_3)

(isA A_1) # ----> there is a initial vertex node

)

(:goal

(exists ( ?A_1001 ?B_1002 ?C_1003 ?D_1004 ) # -----> we want a final world with a square

(and

(isA ?A_1001)

(isB ?B_1002)

(isC ?C_1003)

(isD ?D_1004)

(unido ?A_1001 ?B_1002)

(unido ?B_1002 ?C_1003)

(unido ?C_1003 ?D_1004)

(unido ?D_1004 ?A_1001)

)

)

)

(:metric minimize (total-cost))

)

This language proves to be relatively intuitive, easy to develop and test. However, in Robocomp we opted to do our own planning language: AGM.

###Active Grammar-based Modeling

AGM is the result of Luis Manso’s PhD thesis that “dealt with making software systems for robots more scalable, flexible and easier to develop using software engineering for robotics […] and enhancing active perception in robots using a grammar-based technique named active grammar-based modeling and a specially tailored novelty-detection algorithm named cognitive subtraction”1. To not extend much this post, you can check the working of the AGM on its official website. We will target only that AGM proves to be a useful graphical tool to program rules and to test domains and problems, and its grammar has a reminiscent of the PDDL language (has a AGM to PDDL converter). Let’s look at the same example as before but now in AGM:

This would be the set of rules in a .aggl file:

// START OF THE FILE:

segment : active(1)

{

{

a:A(-175,-15)

}

=>

{

a:A(-415,-5)

b:B(-150,-5)

a->b(union)

}

}

triangle : active(1)

{

{

a:A(-330,-10)

b:B(-70,-15)

a->b(union)

}

=>

{

a:A(-440,170)

c:C(-270,10)

b:B(-70,170)

a->b(union)

b->c(union)

c->a(union)

}

}

square : active(1)

{

{

a:A(-385,80)

c:C(-245,-125)

b:B(-105,80)

a->b(union)

b->c(union)

c->a(union)

}

=>

{

a:A(-460,125)

c:C(-155,-45)

b:B(-150,125)

d:D(-460,-40)

a->b(union)

b->c(union)

c->d(union)

d->a(union)

}

}

The initial world model is stored in a xml file:

<AGMModel>

<symbol id="1" type="A" /> #There is only a vertex node (symbol) with the identifier "1" and te type "A"

</AGMModel>

The goal or target world is stored in another xml file:

<AGMModel>

# NODES:

<symbol id="a" type="A" />

<symbol id="b" type="B" />

<symbol id="c" type="C" />

<symbol id="d" type="D" />

# LINKS BETWEEN NODES (RELATIONSHIPS)

<link src="a" dst="b" label="union" />

<link src="b" dst="c" label="union" />

<link src="c" dst="d" label="union" />

<link src="d" dst="a" label="union" />

</AGMModel>

###Component architecture

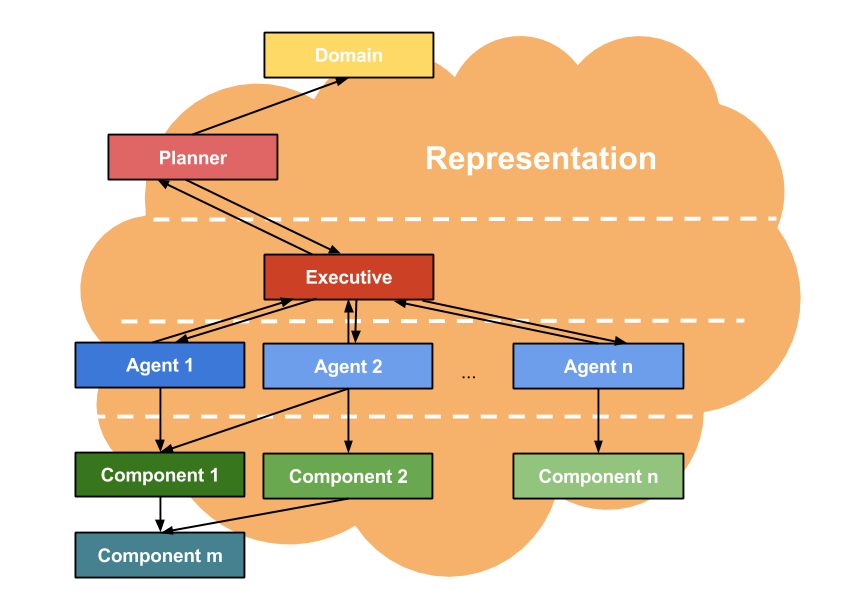

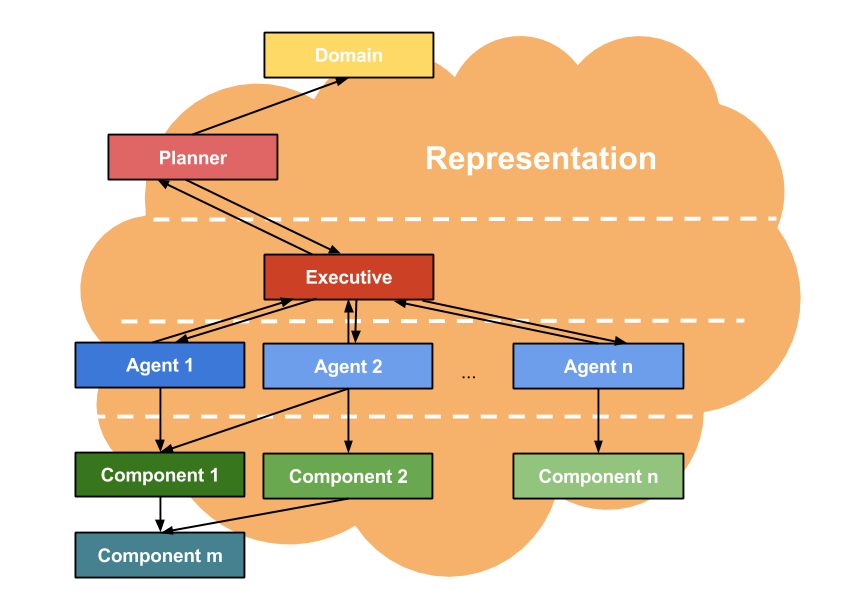

Explained more or less the planners, we will explain the architecture of components developed by robocomp for the robot to be able to carry out actions. Oversimplifying the question in order to that the reader make a clear idea of how the architecture works, we can say that this architecture is divided into three levels:

- First we need a problem domain (a set of rules), like problems in a home environment and a representation of the environment (a model of the robot and its environment).

- In the top we have the AGM planner. Given an initial world and an objective world, it is in charge of generating a plan to reach the goal with the domain defined.

- In the second label, we have a special component, the

executive. Basically he is responsible for transmitting the plan generated by the planner to the lower components. These components perform their actions and alter the representation of the environment. so the executive will have to call the scheduler to verify that these changes on the environment are correct and possible. If the changes are verified, the executive will update the representation.

- In the third label we have the agent components. These are the components that receive the orders of the executive. They uses the operations of the lower component to change the representation. When they finish their execution, they publish the changes in order to be analyzed by the executive.

- In the botton we have the basic components. They are those who perform basic calculations. For example, our

inversekinematic component, our visualik component and our ikGraphGenerator component are in this level.

So the challenge that we have to complete is to create an agent that uses our three inverse kinematics components in order to reach a goal: that the robot take a cup. This component is called graspingAgent and is currently being developed by the laboratory. I would like to delve into its operation, but we still needs to implement many things and GSoC is coming to an end :(

It’s a shame to have to say goodbye with the work so close to being finished. But it doesn’t matters, the next year the robot will be serving coffee to Robolab guys XD.

Bye!

19 Aug 2015

Experience

It has been a quite a ride through this Google Summer of Code. Writing a completely new library with complete building framework/rest framework for documentation or tutorial/and Doxygen framework for auto documentation-class diagrams was challenging. It was equally exciting as well. Because of this I believe that I have acquired quite a good ‘library maintainer/admin’ skills. I will continue contributing into this library after the finish of this GSoC.

After the challenges in building library support tools, the next major challenge was library design. Since, there was no previous ‘coding flavor/design’ I had to come up with the polymorphic and repeatable class design. There was so much confusion in choosing one alternative among the so many choices of good design. While the progress of the library I had to redesign the framework, and and remove structures, include namespaces and several things. I initially had thought that the design will be pretty much stable after the first month, which was not true. I still feel that the main design may need to be changed in the future to have a more logical structure. I hope this constant effort of keeping a good design will be helpful for the library users, and in the end, won’t end up with an unstructured library like OpenCV. In the future I’ll always keep an eye open for the design in general.

Now coming to the actual work of implementing different algorithm, I had really good experience in getting my hands dirty with variety of popular object detection methods. This was exactly what I had thought from this project. Taking out three months and working on the popular methods of your research topic is probably important and I hope that I’ll make a good us of this in the future.

Learning

Here I’ll point out some of the tools and resources I have used while building the library.

####CMake building framework:

I read and used ideas from the CMakeLists files of VTK, pcl and OpenCV (not that much); and chose stuffs among them depending what I thought was interesting and also modified them according to my needs. But in general, I used PCL cmake framework as my major reference.

####Library design:

I have always found the design of VTK, beautiful; so chose it to get the polymorphic design of the classes. Even though fully templated policy based design is faster than polymorphic classes, I chose the polymorphic one as it gives way more flexibility without cluttering the design (ideas taken from vtk). I still am not sure if the performance loss through this design will affect in the future.

####Algorithms:

I had a good background in PCL, so Point Cloud based detection was not difficult and used their wonderful 3d_recognition_framework in my backend. Detection based on 2D features is my own contribution and other 2D global detectors (like HOG) was pretty straightforward from OpenCV.

One good learning was the implementation of HOG Trainer which I worked on few open source code and modified them according to my own needs (like hard negative training etc).

##Future

This project does not ends with the end of GSoC. I plan to do the following in the short term future:

- Host a website as a homepage and links to documentation/tutorials etc.

- Identify how is the website automatically updated with a push in previous libraries like PCL etc. They probably use some demon which runs everyday. Learn and implement it.

- Improve the documentations, write some descriptive tutorials.

- Properly launch the library, with its website; first among the colleagues of our lab; then in public blogs.

19 Aug 2015

Contributions after Mid-term

Following are the contributions towards the project after the mid-term evaluations:

-

HOG based detection (with demo).

-

Face-recognition: training as well as recognition (with demo).

-

Cascade based detection (with demo).

-

Functionality for confidence in a detection (to handle uncertainty).

That concluded the functionality of whatever planned for this summer of code. Other than the planned work, I included some other new functionality which came in between and I thought was required. The other additions are:

-

Addition of two types of detection functions for every detection class.

a. detectOmni : This is the function whose purpose is to detect an object in an entire scene. Thus, other than the type of detection we also have information about the location of the detection w.r.t. the scene. This was the only function previously implemented.

b. detect : The purpose of this function is to perform detection on a segmented scene or an ‘object candidate’. i.e. the entire scene is considered as an ‘object’ or an detection. This function was an extra addition for most of the classes. For global descriptor based classes like ODHOGDetector this function came very naturally.

-

Standardized the training database:. Each detection class identifies its own database (which is a unique folder as of now). Training data of all classes are now put together under a single ‘trained_data’ directory and the rest is resolved by the class automatically.

-

The class ODDetectorMultiAlgo: This is one of the most interesting class and interesting contribution in this project. The idea is to run multiple detection algorithm on a same segmented or unsegmented scene (i.e. run both detect and detectOmni function) and provide the result. That is, using this class one can do object detection/recognition using multiple algorithms and provide outcome of detections (eg. people detected by HOG, face detected by Cascade, bottle detected PnPRansac in a same image). Because of the nice polymorphic design of the detection classes, one can use the concept easily with any number of detection classes with their own parameters, but with ODDetectorMultiAlgo one can only take benefit of the default parameters of the included classes.

-

HOG training: There are no standard training module for training HOG (in OpenCV or in other standard library) and people are mostly confused in training svm with the HOG detector available from OpenCV. This formed a motivation for completing the HOG pipeline and provide a training module. The crucial contribution includes hard negative training mode where the training is repeated with hard examples or false positive windows as negative windows. I hope that this will be really a helpful contribution for the computer vision community.

Design changes, learning resources, and overall learning experiences:

In the next blog I’ll add the different sources I used to design and implement the above tasks and the things I learnt in this process.

16 Aug 2015

Full object manipulation system : In this post we will describe the full system developed for manipulating objects using a robotic arm. We start at the highest level, VisualIK (the correction system), and we will go down to the base of the system, the IK (which calculates the final angle of the joints of the robotic arm).

All the components that will be described below implement the InverseKinematics interface. This interface is defined by a series of data structures:

Pose6D: It represents a pose with three translations and three rotations [x, y, z, rx, ry, rz]WeightVector: It represents the weight vector of each element of Pose6D. This will help us later in the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm.TargetState: It is the state when the targets reach the end of their execution by ik. It has some information like the elapsed time, the final error in translations and rotations and the values of each joint.Axis: This structure represents the Cartesian axes. It is necessary for certain special types of targets.Motor: This structure stores the name and the angular value of a motor of the kinematic chain.

Also, the interface defines a number of methods:

getTargetState: this method returns the state of one target, given the name of the robot part that executed the target and the numerical identifier of the target.getPartState: this method returns the state (if the part has pending targets or not) of one of the robot part (RIGHTARM, LEFTARM or HEAD).setTargetPose6D: This method is used to send targets to the ik. We need to indicate the part of the robot that will execute the target, the pose of the target and the weight vector of the pose. It returns the identifier of the target.setTargetAlignaxis: This method sends a special target for the IK. This target is achieved by aligning the end effector to the target axes. We must indicate the the part of the robot that will execute the target, the pose and the axes. It returns the identifier of the target.setTargetAdvanceAxis: This method sends another special target for the IK. The goal is that the end effector advance along a vector in the Cartesian system. We must indicate the part of the robot that will execute the target, the axes of the vector and the dist to advance. Like always, it return the identifier of the target.goHome: this method send a robot part to the idle position.stop: this method abort the execution of the targets of one of the robot part.setJoint: this method changes the angular value of one of the joint of the kinematic chain.setFingers: this method opens and closes the fingers of the end effector.

Now, we will describe the basic operation of our components.

###The visualIK component

The old VisualBIK component has been reorganized, resulting in the current visualik component. The basic principle of operation of the component remains, adding some improvements and changing its communication with the inversekinematics component, by the ikGraphGenerator component.

Its goal remains the same, correct errors produced by the inaccuracies of the joints in the IK. To this end, it bases its operation on a state machine:

IDLE: It is the resting state of visualik. The component is waiting to receive a target through one of the methods of its interface. When a target comes through the interface (stored in the currentTarget variable), the state machine switches to INIT_BIK and prepares the global variables for the execution of correction.INIT_BIK: in this state, the visualik applies an initial correction to the target (Ec). This correction is based on experience in the correction of previous targets, so the first correction, having no previous experience, will be zero. Then, it sends the target to his proxy of kinematic, the ikGraphGenerator component. Finally, the state of the machine is changed to WAIT_BIK.WAIT_BIK: in this state, the visualik waits the end of execution of the target by the ikGraphGenerator. When the ikGraphGenerator finishes executing the target, the visualik changes his state to CORRECT_ROTATION.CORRECT_ROTATION: It is the latest machine status. In this state is when the visualik does all the calculations in order to correct the deviations and errors of the joints. The procedure is simple: a) by apriltags, the visualik calculates the visual pose of the end effector; b) then, it computes the error vector between the visual pose and the target pose (Ev); c) with this error vector Ev, the visualik corrects the target pose and sends the new position to the ikGraphGenerator component; d) this process is repeated until the error achieved in translation and rotation is less than a predetermined threshold; e) finally the visualik calculates the error vector between the original target and the last corrected target (Ec), with this error the component realizes the first correction in INIT_BIK.

Here there is a scheme of the procedure performed by the visualik. It is very summarized to facilitate the understanding of the procedure by the reader:

1: procedure VISUAL CALIBRATION

2: Xt = TargetArrives()

3: Ct = Xt + Ec

4: sendTargetToGIK(Ct)

5: Xv = getAprilTagPose(robot)

6: while (Ev = Xv- Xt) > threshold ^¬ timeOut() do

7: Xi = getInternalPose(robot)

8: Xc = Xi + Ev

9: sendTargetToGIK(Xc)

10: Xv = getAprilTagPose(robot)

11: end while

12: Ec = Xc - Xt

13: end procedure

Like all components developed by robocomp, the visualik needs a configuration file in which the components required (the ikGraphGenerator) and the components to subscribe (the apriltagsComp) and other configuration parameters are determined. In this case, a configuration file may have the following elements:

CommonBehavior.Endpoints=tcp -p 14537

# Endpoints for implemented interfaces:

InverseKinematics.Endpoints=tcp -p 10242

# Endpoints for interfaces to subscribe:

AprilTagsTopic.Endpoints=tcp -p 12938

# Proxies for required interfaces

InverseKinematicsProxy =inversekinematics:tcp -h localhost -p 10241 # `ikGraphGenerator`

InnerModel=/home/robocomp/robocomp/components/robocomp-ursus-rockin/etc/ficheros_Test_VisualBIK/ursus_bik.xml # the internal model of the robot environment

# This property is used by the clients to connect to IceStorm.

TopicManager.Proxy=IceStorm/TopicManager:default -p 9999

Ice.Warn.Connections=0

Ice.Trace.Network=0

Ice.Trace.Protocol=0

Ice.ACM.Client=10

Ice.ACM.Server=10

###The ikGraphGenerator component

As we explain in the previous post, the ikGraphGeneratorcomponent creates and stores a graph representing the work 3D space of the arm, where each node stores the euclidean space pose of the end effector and the configuration of the joints that compose the arm. So the ikGraphGenerator waits until the visualik send a target to him through the InverseKinematics interface. In this moment, the ikGraphGenerator performs four steps:

- the component searches the node A whose pose is closest to the initial end effector pose and moves the arm there.

- the component finds in the graph the node B whose pose is closest to the target position, disabling those nodes which would make the robot’s arm collide with external objects.

- the component computes the shortest path between the node A and the node B and moves the end effector among the nodes to reach the node B.

- Finally, the component moves from the graph to the actual target sending the original target to the

inversekinematiccomponent and taking the final values of the joints.

The ikGraphGeneratorneeds a config file too:

CommonBehavior.Endpoints=tcp -p 14536

# Endpoints for implemented interfaces:

InverseKinematics.Endpoints=tcp -p 10241

InnerModel=/home/robocomp/robocomp/components/robocomp-ursus/etc/ursus.xml # the internal model of the robot environment

# Proxies for required interfaces

InverseKinematicsProxy = inversekinematics:tcp -h localhost -p 10240

JointMotorProxy = jointmotor:tcp -h localhost -p 20000

Ice.Warn.Connections=0

Ice.Trace.Network=0

Ice.Trace.Protocol=0

Ice.ACM.Client=10

Ice.ACM.Server=10

###The inversekinematic component

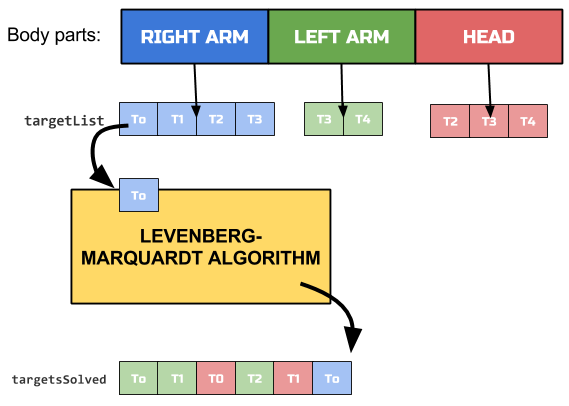

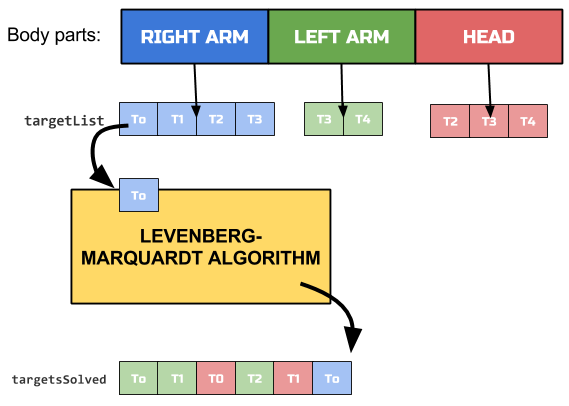

Finally, we will explain the basic component of the system, the inversekinematic component. As we said in the second post, this component receives three types of targets through the InverseKinematics interface:

POSE6D: the typical target with translations and rotations [tx, ty, tz, rx,ry, rz]. The end effector has to be positioned at coordinates (tx, ty, tz) of the target and align their rotation axes with the target, specified in (rx, ry, rz). This target arrives from the method setTargetPose6D.ADVANCEAXIS: its goal is to move the end effector of the robot along a vector. This target arrives from the method setTargetAdvanceAxis.ALIGNAXIS: Its goal is that the end effector has the axes aligned with the target. This target arrives from the method setTargetAlignaxis.

Targets received are stored into the queues of the corresponding robot part and they are executed by order of arrival. When the ik ends the execution of one target, it stores the target into the solved targets queue:

The config file of the inversekinematiccomponent is the next:

CommonBehavior.Endpoints=tcp -p 12207

# Endpoints for implemented interfaces:

InverseKinematics.Endpoints=tcp -p 10240

# Kinematic chain lists: they stores the joints names.

RIGHTARM=rightShoulder1;rightShoulder2;rightShoulder3;rightElbow;rightForeArm;rightWrist1;rightWrist2

RIGHTTIP=grabPositionHandR # end effector of the RIGHTARM

LEFTARM=leftShoulder1;leftShoulder2;leftShoulder3;leftElbow;leftForeArm;leftWrist1;leftWrist2

LEFTTIP=grabPositionHandL

HEAD=head_yaw_joint;head_pitch_joint

HEADTIP=rgbd_transform

InnerModel=/home/robocomp/robocomp/components/robocomp-ursus/etc/ursus.xml #Internal model of the robot environment

# Proxies for required interfaces

JointMotorProxy = jointmotor:tcp -h localhost -p 20000

TopicManager.Proxy=IceStorm/TopicManager:default -p 9999

Ice.Warn.Connections=0

Ice.Trace.Network=0

Ice.Trace.Protocol=0

Ice.ACM.Client=10

Ice.ACM.Server=10

When visualik and ikGraphGenerator components submit their targets to the immediately below component, they store the identifier of the target and are waiting until the target be resolved, calling the method getTargetState. So, when the inversekinematic component ends one target execution, the ikGraphGenerator moves the arm with the values given by the inversekinematic component and then, the visualik continues with the corrections.

Having explained the handling system, the next post will explain the planning system developed by ROBOLAB to plan the robot’s actions.

Bye!